Reflections and selected highlights from the Fantastic Futures 2023 conference, held at the Internet Archive Canada's building in Vancouver and Simon Fraser University; full programme; videos will be coming soon.

A TL;DR is that it's incredible how many of the projects discussed wouldn't have been possible (or less feasible) a year ago. Whisper and ChatGPT (4, even more than 3.5) and many other new tools really have brought AI (machine learning) within reach. Also, the fact that I can *copy and paste text from a photo* is still astonishing. Some fantastic parts of the future are already here.

Other thinking aloud / reflections on themes from the event: the gap between experimentation and operationalisation for AI in GLAMs is still huge. Some folk are desperate to move onto operationalisation, others are enjoying the exploration phase – thinking about it, knowing where you and your organisation each stand on that could save a lot of frustration! Bridging it is possible, but it takes dedicated resources (including quality checking) from multi-disciplinary teams, and probably the goal has to be big and important enough to motivate all the work required. In examples discussed at FF2023, the scale of the backlog of collection items to be processed is that big important thing that motivates work with AI.

It didn't come up as directly, perhaps because many projects are still pilots rather than in production, but I'm very interested in the practical issues around including 'enriched' data from AI (or crowdsourcing) in GLAM collections management / cataloguing systems. We need records that can be enriched with transcriptions, keywords and other data iteratively over time, and that can record and display the provenance of that data – but can your collections systems do that?

Making LLMs stick to content in the item is hard, 'hallucinations' and loose interpretations of instructions are an issue. It's so useful hearing about things that didn't work or were hard to get right – common errors in different types of tools, etc. But who'd have thought that working with collections metadata would involve telling bedtime stories to convince LLMs to roleplay as an expert cataloguer?

Workflows are vital! So many projects have been assemblages of different machine learning / AI tools with some manual checking or correction.

A general theme in talks and chats was the temptation to lower 'quality' to be able to start to use ML/AI systems in production. People are keen to generate metadata with the imperfect tools we have now, but that runs into issues of trust for institutions expected to publish only gold standard, expert-created records. We need new conventions for displaying 'data in progress' alongside expert human records, and flexible workflows that allow for 'humans in the loop' to correct errors and biases.

If we are in an 'always already transitional' world where the work of migrating from one cataloguing standard or collections management tool to another is barely complete before it's time to move to the next format/platform, then investing in machine learning/AI tools that can reliably manage the process is worth it.

'Data ages like wine, software like fish' – but it used to take a few years for software to age, whereas now tools are outdated within a few months – how does this change how we think about 'infrastructure'? Looking ahead, people might want to re-run processes as tools improve (or break) over time, so they should be modular. Keep (and version) the data, don't expect the tool to be around forever.

Update to add: Francesco Ramigni posted on ACMI at Fantastic Futures 2023, and Emmanuelle Bermès posted Toujours plus de futurs fantastiques ! (édition 2023).

FF2023 workshops

I ran a workshop and went to two others the day before the conference proper began. I've put photos from the workshop I ran with Thomas Padilla (originally proposed with Nora McGregor and Silvia Gutiérrez De la Torre too) on Co-Creating an AI Responsive Information Literacy Curriculum workshop on Flickr. You can check out our workshop prompts and links to the 'AI literacy' curricula devised by participants.

Fantastic Futures Day 1

Thomas Mboa opens with a thought-provoking keynote. Is AI in GLAMs a Pharmakon (a purification ritual in ancient Greece where criminals were expelled)? Phamakon can mean both medicine and poison.

And discusses AI as technocoloniality e.g.Libraries in the age of technocoloniality: Epistemic alienation in African scholarly communications

Mboa asks / challenges the GLAM community:

- Can we ensure cultural integrity alone, from our ivory tower?

- How can we involve data-providers communities without exploiting them?

- Al feeds on data, which in turn conveys biases. How can we ensure the quality of data?

Cultural integrity is a measure of the wholeness or intactness of material, whether it respects and honours traditional ownership, traditions and knowledge

Mboa on AI for Fair Work – avoiding digital extractivism; the need for data justice e.g. https://www.gpai.ai/projects/future-of-work/AI-for-fair-work-report2022.pdf.

Thomas Mboa finishes with 'Some Key actions to ensure responsible use of Al in GLAM':

- Develop Ethical Guidelines and Policies

- Address Bias and Ensure Inclusivity

- Enhance Privacy and Data Security

- Balance Al with Human Expertise

- Foster Digital Literacy and Skills Development

- Promote Sustainable and Eco-friendly Practices

- Encourage Collaboration and Community Engagement

- Monitor and Evaluate Al Impact:

- Intellectual Property and Copyright Considerations:

- Preserve Authenticity and Integrity]

I shared lessons for libraries and AI from Living with Machines then there was a shared presentation on Responsible AI and governance – transparency/notice and clear explanations; risk management; ethics/discrimination, data protection and security.

Mike Trizna (and Rebecca Dikow) on the Smithsonian's AI values statement. Why We Need an Al Values Statement – everyone at the Smithsonian involved in data collection, creation, dissemination, and/or analysis is a stakeholder – Our goal is to aspirationally and proactively strive toward shared best practices across a distributed institution. All staff should feel like their expertise matters in decisions about technology.

Jill Reilly mentioned 'archivists in the loop' and 'citizen archivists in the loop' at NARA, and Inventory of NARA Artificial Intelligence (AI) Use Cases

From Bart Murphy (and Mary Sauer Games)'s talk it seems OCLC are really doing a good job operationalising AI to deduplicate catalogue entries at scale, maintaining quality and managing cost of cloud compute; also keeping ethics in mind.

Next, William Weaver on 'Navigating AI Advancements with VoucherVision and the Specimen Label Transcription Project' – using OCR to extract text from digitised herbarium sheets (vouchers) and machine learning to parse messy OCR. More solid work on quality control! Their biggest challenge is 'hallucinations' and also LLM imprecision in following their granular rules. More on this at The Future of Natural History Transcription: Navigating AI advancements with VoucherVision and the Specimen Label Transcription Project (SLTP).

Next, Abigail Potter and Laurie Allen, Introducing the LC Labs Artificial Intelligence Planning Framework. I love that LC Labs do the hard work of documenting and sharing the material they've produced to make experimentation, innovation and implementation of AI and new technologies possible in a very large library that's also a federal body.

Abby talked about their experiments with generating catalogue data from ebooks, co-led with their cataloguing department.

A panel discussed questions like: how do you think about "right sizing" your Al activities given your organizational capacity and constraints? How do you think about balancing R&D / experimentation with applying Al to production services / operations? How can we best work with the commercial sector? With researchers? What do you think the role of LAMs should be within the Al sector and society? How can we leverage each other as cultural heritage institutions?

I liked Stu Snydman's description of organising at Harvard to address AI with their values: embrace diverse perspectives, champion access, aim for the extraordinary, seek collaboration, lead with curiosity. And Ingrid Mason's description of NFSA's question about their 'social licence' (to experiment with AI) as an 'anchoring moment'. And there are so many reading groups!

Some of the final talks brought home how much more viable ChatGPT 4 has made some tasks, and included the first of two projects trying to work around the fact that people don't provide good metadata when depositing things in research archives.

Fantastic Futures Day 2

Day 2 begins with Mike Ridley on 'The Explainability Imperative' (for AI; XAI). We need trust and accountability because machine learning is consequential. It has an impact on our lives. Why isn't explainability the default?

His explainability priorities for LAM: HCXAI; Policy and regulation; Algorithmic literacy; Critical making.

Mike quotes 'Not everything that is important lies inside the black box of AI. Critical insights can lie outside it. Why? Because that's where the human are.' Ehsan and Riedl.

Mike – explanations should be actionable and contestable. They should enable reflection, not just acquiescence.

Algorithm literacy for LAMs – embed into information literacy programmes. Use algorithms with awareness. Create algorithms with integrity.

Policy and regulation for GLAMs – engage with policy and regulatory activities; insist on explainability as a core principle; promote an explanatory systems approach; champion the needs of the non-expert, lay person.

Critical making for GLAMs – build our own tools and systems; operationalise the principles of HCXAI; explore and interrogate for bias, misinformation and deception; optimise for social justice and equity

Mike quotes: "Technology designers are the new policymakers; we didn't elect them but their decisions determine the rules we live by." Latanya Sweeney (Harvard University, Director of the Public Interest Tech Lab)

Next: shorter talks on 'AI and collections management'. Jon Dunn and Emily Lynema shared work on AMP, an audiovisual metadata platform, built on https://usegalaxy.org/ for workflow management. (Someone mentioned https://airflow.apache.org/ yesterday – I'd love to know more about GLAMs experiences with these workflow tools for machine learning / AI)

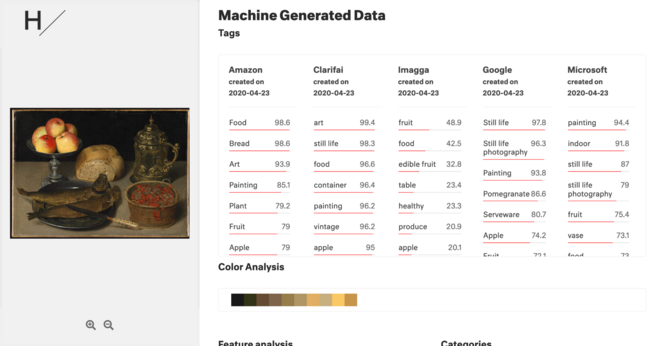

Nice 'AI explorer' from Harvard Art Museums https://ai.harvardartmuseums.org/search/elephant presented by Jeff Steward. It's a really nice way of seeing art through the eyes of different image tagging / labelling services like Imagga, Amazon, Clarifai, Microsoft.

(An example I found: https://ai.harvardartmuseums.org/object/228608. Showing predicted tags like this is a good step towards AI literacy, and might provide an interesting basis for AI explainability as discussed earlier.)

Scott Young and Jason Clark (Montana State University) shared work on Responsible AI at Montana State University. And a nice quote from Kate Zwaard, 'Through the slow and careful adoption of tech, the library can be a leader'. They're doing 'irresponsible AI scenarios' – a bit like a project pre-mortem with a specific scenario e.g. lack of resources.

Emmanuel A. Oduagwu from the Department of Library & Information Science, Federal Polytechnic, Nigeria, calls for realistic and sustainable collaborations between developing countries – library professionals need technical skills to integrate AI tools into library service delivery; they can't work in isolation from ICT. How can other nations help?

Generative AI at JSTOR FAQ https://www.jstor.org/generative-ai-faq from Bryan Ryder / Beth LaPensee's talk. Their guiding principles (approximately):

- Empowering researchers: focus on enhancing researchers' capabilities, not replacing their work

- User-centred approach – technology that adapts to individuals, not the other way around

- Trusted and reliable – maintain JSTOR's reputation for accurate, trustworthy information; build safeguards

- Collaborative development – openly and transparently with the research community; value feedback

- Continuous learning – iterate based on evidence and user input; continually refine

Michael Flierl shared a bibliography for Explainable AI (XAI).

Finally, Leo Lo and Cynthia Hudson Vitale presented draft guiding principles from the US Association of Research Libraries (ARA). Points include the need to include human review; prioritise the safety and privacy of employees and users; prioritise inclusivity; democratise access to AI and be environmentally responsible.